Difference between revisions of "Building dictionaries"

(Documentation in English) |

|||

| Line 240: | Line 240: | ||

[[Category:Documentation]] |

[[Category:Documentation]] |

||

[[Category:Writing dictionaries]] |

[[Category:Writing dictionaries]] |

||

[[Category:Documentation in English]] |

|||

Revision as of 18:21, 3 September 2011

Some of you have been brave enough to start to write new language pairs for Apertium. That makes me (and all of the Apertium troop) very happy and thankful, but, most importantly, makes Apertium useful to more people.

This time I want to share some lessons I have learned after building some dictionaries: the importance of frequency estimates. For the new pairs to have the best possible coverage with a minimum of effort, it is very important to add words and rules in decreasing frequency, starting with the most frequent words and phenomena.

The reason that words should be added in order of frequency is quite intuitive, the higher the frequency, the more likely the word is to appear in the text you are trying to translate (see below for Zipf's law).

For example in English you can almost be sure that the words "the" or "a" will appear in all but the most basic sentences, however how many times have you seen "hypothyroidism" or "obelisk" written? The higher the frequency the word, the more you "gain" from adding it.

Frequency

A person's intuition on which words are important of frequent can be very deceptive. Therefore, the best one can do is collect a lot of text (millions of words if possible) which is representative of what one wants to translate, and study the frequencies of words and phenomena. Get it from Wikipedia, or from newspaper, or write a robot that harvests it from the web.

It is quite easy to make a crude "hit parade" of words using a simple Unix command sequence (a single line)

$ cat mybigrepresentative.txt | tr ' ' '\012' | sort -f | uniq -c | sort -nr > hitparade.txt

[I took this from Unix for Poets I think]

Of course, this may be improved a lot but serves for illustration purposes.

You will find interesting properties in this list.

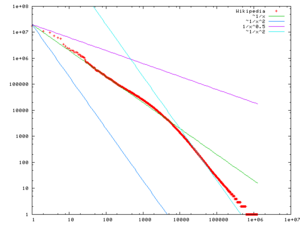

One is that multiplying the rank of a word by its frequency, you get a number which is pretty constant. That's called Zipf's Law.

The other one is that half of the list are "hapax legomena" (words that appear only once).

And third, with about 1000 words you may have 75% of the text covered.

So use lists like these when you are building dictionaries.

If one of your language is English, there are interesting lists:

But bear in mind that these lists are also based on a particular usage model of English, which is not "natural occurring" English.

The same applies for other linguistic phenomena. Linguists tend to focus on very infrequent phenomena which are key to the identity of a language, or on what is different between languages. But these "jewels" are usually not the "building blocks" you would use to build translation rules. So do not get carried away. Trust only frequencies and lots of real text...

Corpus catcher

Wikipedia dumps

For help in processing them see:

The dumps need cleaning up (removing Wiki syntax and XML etc.), but can provide a substantial amount of text for both frequency analysis, and sentences for POS tagger training. It can take some work, and isn't as easy as getting a nice corpus, but on the other hand they're available in ~270 languages.

You'll want the one entitled "Articles, templates, image descriptions, and primary meta-pages. -- This contains current versions of article content, and is the archive most mirror sites will probably want."

Something like (for Afrikaans):

$ bzcat afwiki-20070508-pages-articles.xml.bz2 | grep '^[A-Z]' | sed 's/$/\n/g' | sed 's/\[\[.*|//g' | sed 's/\]\]//g' | sed 's/\[\[//g' | sed 's/&.*;/ /g'

Will give you approximately useful lists of one sentence per line (stripping out most of the extraneous formatting). Note, this presumes that your language uses the Latin alphabet, if it uses another writing system, you'll need to change that.

Try something like (for Afrikaans):

$ bzcat afwiki-20070508-pages-articles.xml.bz2 | grep '^[A-Z]' | sed 's/$/\n/g' | sed 's/\[\[.*|//g' | sed 's/\]\]//g' | sed 's/\[\[//g' | sed 's/&.*;/ /g' | tr ' ' '\012' | sort -f | uniq -c | sort -nr > hitparade.txt

Once you have this 'hitparade' of words, it is first probably best to skim off the top 20—30,000. Into a separate file.

$ cat hitparade.txt | head -20000 > top.lista.20000.txt

Now, if you already have been working on a dictionary then the chances are that there will exist in this 'top list' words you have already added. You can remove word forms you are already able to analyse using (for example Afrikaans):

$ cat top.lista.20000.txt | apertium-destxt | lt-proc af-en.automorf.bin | apertium-retxt | grep '\/\*' > words_to_be_added.txt

(here lt-proc af-en.automorf.bin will analyse input stream of Afrikaans words and put an asterisk * on those it doesn't recognise)

For every 10 words or so you add, its probably worth going back and repeating this step, especially for highly inflected languages — as one lemma can produce many word forms and the wordlist is not lemmatised.

Getting cheap bilingual dictionary entries

A cheap way of getting bilingual dictionary entries between a pair of languages is as follows:

First grab yourself a wordlist of nouns in language x, for example, grab them out of the Apertium dictionary you are using:

$ cat <monolingual dictionary> | grep '<i>' | grep '__n\"' | awk -F'"' '{print $2}'

Next, write a basic script, something like:

#!/bin/sh

#language to translate from

LANGF=$2

#language to translate to

LANGT=$3

#filename of wordlist

LIST=$1

for LWORD in `cat $LIST`; do

TEXT=`wget -q http://$LANGF.wikipedia.org/wiki/$LWORD -O - | grep 'interwiki-'$LANGT`;

if [ $? -eq '0' ]; then

RWORD=`echo $TEXT |

cut -f4 -d'"' | cut -f5 -d'/' |

python -c 'import urllib, sys; print urllib.unquote(sys.stdin.read());' |

sed 's/(\w*)//g'`;

echo '<e><p><l>'$LWORD'<s n="n"/></l><r>'$RWORD'<s n="n"/></r></p></e>';

fi;

sleep 8;

done

Note: The "sleep 8" is so that we don't put undue strain on the Wikimedia servers

And save it as iw-word.sh, then you can use it at the command line:

$ sh iw-word.sh <wordlist> <language code from> <language code to>

e.g. to retrieve a bilingual wordlist from English to Afrikaans, use:

$ sh iw-word.sh en-af.wordlist en af

The method is of variable reliability. Reports of between 70% and 80% accuracy are common. It is best for unambiguous terms, but works ok where terms retain ambiguity through languages.

Any correspondences produced by this method must be checked by native or fluent speakers of the language pairs in question.

Monodix

- Main article: Monodix

If the language you're working with is fairly regular, and noun inflection is quite easy (for example English or Afrikaans) then the following script may be useful:

You'll need a large wordlist (of all forms, not just lemmata) and some existing paradigms. It works by first taking all singular forms out of the list, then looking for plural forms, then printing out those which have both singular and plural forms in Apertium format.

Note: These will need to be checked, as no language is that regular.

# set this to the location of your wordlist

WORDLIST=/home/spectre/corpora/afrikaans-meester-utf8.txt

# set the paradigm, and the singular and plural endings.

PARADIGM=sa/ak__n

SINGULAR=aak

PLURAL=ake

# set this to the number of characters that need to be kept from the singular form.

# e.g. [0:-1] means 'cut off one character', [0:-2] means 'cut off two characters' etc.

ECHAR=`echo -n $SINGULAR | python -c 'import sys; print sys.stdin.read().decode("utf8")[0:-1];'

PLURALS=`cat $WORDLIST | grep $PLURAL$`

SINGULARS=`cat $WORDLIST | grep $SINGULAR$`

CROSSOVER=""

for word in $PLURALS; do

SFORM=`echo $word | sed "s/$PLURAL/$SINGULAR/g"`

cat $WORDLIST | grep ^$SFORM$ > /dev/null

# if the form is found then append it to the list

if [ $? -eq 0 ]; then

CROSSOVER=$CROSSOVER" "$SFORM

fi

done

# print out the list

for pair in $CROSSOVER; do

echo ' <e lm="'$pair'"><i>'`echo $pair | sed "s/$SINGULAR/$ECHAR/g"`'</i><par n="'$PARADIGM'"/></e>';

done

See also

Further reading

- Mark Pagel, Quentin D. Atkinson & Andrew Meade (2007) "Frequency of word-use predicts rates of lexical evolution throughout Indo-European history". Nature 449, 665

- "Across all 200 meanings, frequently used words evolve at slower rates and infrequently used words evolve more rapidly. This relationship holds separately and identically across parts of speech for each of the four language corpora, and accounts for approximately 50% of the variation in historical rates of lexical replacement. We propose that the frequency with which specific words are used in everyday language exerts a general and law-like influence on their rates of evolution."